Episode 2 - Sonic Resonance

Download it here

Vince stood thumbing through the plastic-sleeved albums in the plywood bins of Somewhere Records. Tuesdays were chill. A respite from the late week and weekend shows that pulled in folks from across the city. The place was a glowing oasis on the eastside, part art gallery, bar, music venue, and record shop. It has stood strong going on ten years. Today you could almost hear the hum of the mechanical system floating over Coltrane playing low on the Technics 1200.

A guy, younger than Vince, worked through the 90’s Hip-Hop section across the aisle while a couple sat at the bar across from the stacks sipping coffee lost in conversation. Vince is on the shorter side, thin and with the most generous smile. His thinning curly hair is beginning to show the graying of his years. He is a fixture in the music scene and has been for over 45 years. He still spins, an early evening or a brunch set, but gone are the days of all-nighters and four DJ sets spinning the truths of dance, house and techno.

Today, Vince spends most of his time bringing one of the many derelict neighborhood blocks back to life. Driving down Mack Avenue past Helen Street, there’s a good chance you’ll see him out mowing the grass and weeds, clearing garbage, planting a new tree or shoveling snow. Like so many here, he loves this city and loves his neighborhood. When he’s not huffing bags of trash to the street or helping a neighbor with their siding or rewiring their electrical, he publishes a quarterly journal on Detroit’s electronic music. It showcases new talents, shows, and tells the stories of the founding giants from their early underground days of playing in vacant buildings and warehouses to today’s faraway stadiums, festivals, and island getaways.

There’s a resurgence of the music which started here nearly 50 years ago, some think it coincides with the explosion of youth, artists, and entrepreneurs committing to the city. There’s an energy that fuels the neighborhoods, community gardens, neighbors taking care of neighbors, and small shops and restaurants. Only a couple of miles from the billion-dollar corporate investments of downtown, these neighborhoods still feels like they’re another planet all together. It ain’t easy but there’s a soul to the place unlike anywhere else on earth.

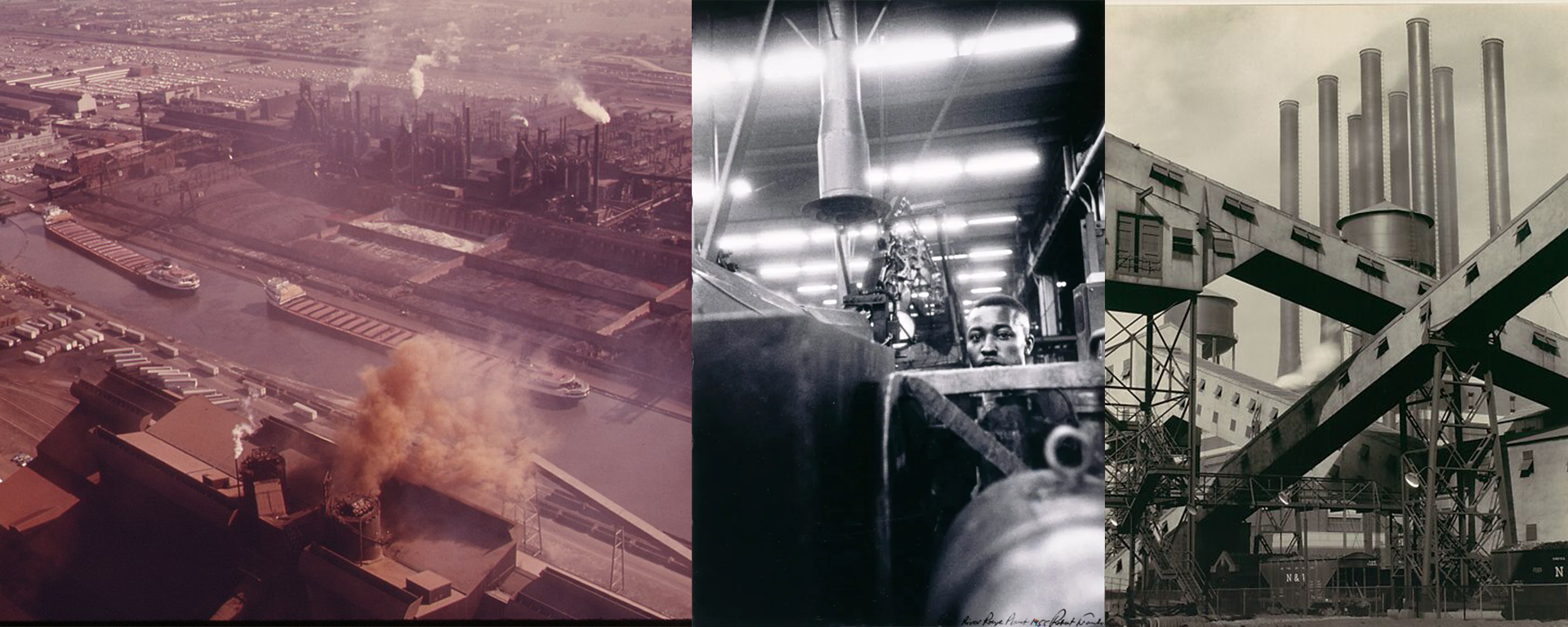

Vince has been here almost from the beginning of this Detroit story. Shortly after high school, he came to Detroit from another struggling rust belt town in the early ‘80’s. Detroit seemed to have more soul or heart or something, Vince didn’t know exactly what it was when he packed up his Chevy Chevette with its crunched left fender and rust beginning to eat at GM’s answer to the oil embargo. He drove up I-75 into town through the welcoming smell of sulphur and the burning refinery gas plumbs igniting the nighttime skies across the 2,000 acres of Ford’s River Rouge. In its day, 100,000 men and women worked three shifts, when Vince went rolling over the skying overpass Rouge had a fraction of that punching the clock. Much of it sat dark, in decay or half demolished. It was a surreal landscape like no other. This 80-mile an hour flying concrete overpass was Detroit’s equivalent of legions passing through a great stone Roman gate into a city of antiquity. This industrial gate was the vaporous cocktail of hydrogen sulfide’s rotten egg, burning tar and ammonia. Welcome to the Motor City 1981.

Living in a small apartment in Palmer Park, the remnants of a great neighborhood, he found his footing. In the early ‘80’s disco, funk and R&B was prevalent, as was punk. Despite Motown moving to LA back in 1972, Detroit was a hotbed of innovative and gritty music. Electrifying Mojo spun on WJLB and his late-night show, Midnight Funk Association, brought an experimental genre-bending mix of funk, new wave and soul to the airwaves. Hell, he’s credited with breaking Prince onto the air. Mojo was playing stuff before anyone knew what it was. Kids, black and white, gay and straight, were in clubs dancing and throwing after-hour parties for 1,000 of their closest friends in vacant warehouses and towers. The underground after-hour scene was serious, partially because then Mayor Coleman Young happened to like a little after-hour entertainment himself. Kenny Collier, known as The Godfather, would spin at Heaven, L’Uomo and Cheeks, sanctuaries for young people out finding themselves. A few years later, Kenny would end up mentoring three young guys from Belleville, a western suburb of Detroit. Those three would go on to change everything about music, and once again, put Detroit at the center of it.

Electrifying Mojo

Vince was witness to it all. He wasn’t one of the stars, but he could hold a room, and he was happy to carry a crate of albums for a fellow artist, get the word out, and just be a positive force for those around him.

With a couple albums under his arm, Vince grabbed a stool at the bar and ordered a beer. As he read the back cover of one of his purchases, the young man from the record stacks approached him and said, “Hey, you’re Vince, right?”

“Ya, that’s me. What going on?” Vince replied.

“I’m Milo, mind if I sit?” Extending his hand to shake Vince’s.

“Sure, what’s up?” Vince asked and Milo pulled himself onto the stool next to Vince.

“You been around awhile I hear, not to be any way, but I understand you’ve been part of the music scene for a long time.” Milo said.

“Ya, ya, you could say that.” Vince said sipping his shell of beer. “From the beginning one might say.”

“Want a beer?” Vince asked.

“Ya, thanks.” Milo accepted and Vince gestured to the barista bartender.

“Mind if I ask, um…ask you something?” Milo asked.

“Of course, no problem. If I can answer it, I’m happy to.” Vince said.

“What was is like?” Milo asked.

“What do you mean?” Vince responded.

“Back in the day, you know when you all were first coming up?” Milo continued.

“Ahh…ya, it was, it was very special. Lotta love.” Vince looked at Milo then turned into his beer. “I was around, riding the coattails of some incredible talent.”

“Must have been something.” Milo said nodding his head as he set his beer down onto the thick paper coaster.

“Ya, it was something else. The music was like nothing else. No one had ever heard beats like that. People went crazy.” Vince said, “There were a couple places that embodied it all, so far ahead of their time. Today, there’s places like this and a handful of others, but back then…well, let’s just say, none of this would exist if it wasn’t for that.”

“You must know these stories. You’re not from around here?” Vince asked.

“Nah, I’m not. I’m just visiting for a while.” Milo said.

Vince looked at him, almost scanning, and said, “You got to know the history, where it all came from. Got to know what came before.”

“Grab your beer and let’s move over there, I’m happy to tell you.” Vince said motioning over to a sitting area surrounded by large paintings of portraits and urban landscapes. They made their way over to a couple couches and sat. Milo attentive sat forward with his knees pressed against the glass top table floating above its rusted scrap steel welded legs.

“What can I tell you really. It was a time that even today you hear people talking about it. It connected us. It gave so many a place to discover themselves, to be true, to push back against all the shit around them. There was something that connected. And, people danced, man serious dancing. You know what I mean?” Vince asked.

“Hey, hey Vince! How you doing?” A voice of a woman interrupted echoing from the entrance.

Vince turned, smiled and got up walking toward the silhouetted figure.

“Stacey, Stacey. How are you?” They hugged. “It has been so long, too long. I’ve missed you.” Vince said.

“I’m sure you’re still moving a million miles an hour. Come on sit for a second.” He continued.

“I don’t have long just stopping by, I got a meeting with some folks about Women on Wax.” Stacey said.

“I love that, good for you.” Vince held her hand in a warm embrace.

“You never age, my god, you look just like you did when we first met. Me, I’m gray as hell.” Vince exclaimed.

“O’ Baby, you know I just keep moving.” Stacey responded.

Milo smiled sheepishly, feeling like an intruder.

“This young man is Milo. He’s from… hell I don’t even know where you’re from…he’s interested in the music and the old scene. I was just telling him about what it was like back then. How the city was. How we all got started. You know…you were right there.”

“Milo, this is Stacey, she made it all happen back in the day and is still making it happen.” Vince said. “This lady is the Godmother of House!”

“You can’t be any older than my daughter, and you’re into this? Good for you.” Stacey said.

“It’s a real pleasure.” Milo said as he stood to shake her hand. Stacey had a striking presence, her hair stood like a noble crown, her sunburst earrings and chainmail jacket glistened and popped over her black top, jeans and boots.

“Got to know your history, no doubt. House, techno it all came from here. No one can deny that. But you got to know your roots.” Stacey said looking at the young man as her smile radiated across her espresso skin as her dark eyes shined though her big blue frames.

Vince would go on to explain.

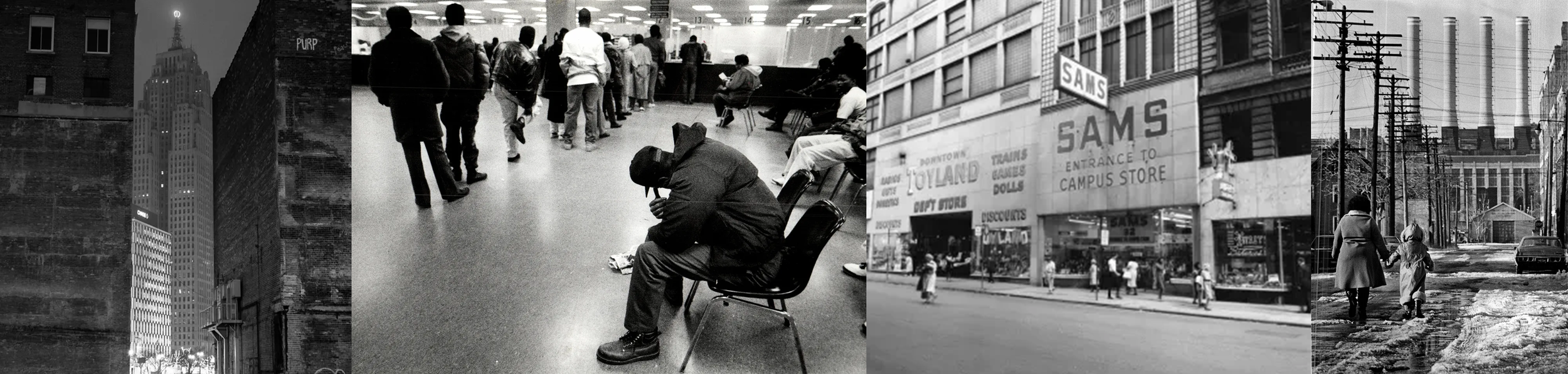

“It’s the all-too-often-mentioned story of a city burned out, block after block of smoldering and abandoned homes. Empty lots like missing teeth of a broad smile filled with overgrown weeds, piles of tires and garbage were the neighborhood landscape in many parts of town. The downtown, once vibrant, once the most successful city on the country, nearly 2 million people was a carcass of empty buildings, boarded up storefronts, and once great architectural symbols of economic might had a single light left on here or there climbing up their façades.

Now, just under 650,000 people. Barely 6,000 lived downtown. Ya, you could drive the wrong way down one-way streets without a fear of seeing an oncoming car, or even a cop. It was a desert, abandoned and decaying. A city center that was dead and had been dying since the 1967 riots. Racism was deep and blame went all around. Spoils of an era of prosperity and privilege, but not for all. A great divide of opportunities, a racist police department, and the Grosse Pointes and Bloomfields where parents and the grandparents wouldn’t even venture downtown other than for a symphony performance, valet included.

Sure, downtown would blow up during sports events, the Auto Show and the fireworks every July. But most days, people drove in for their 9-5 and then would hightail it back to the burbs up the Lodge or 75. There wasn’t even grocery store to speak of, other than the stained asbestos tiled floor of Paul’s Cut-rate Drugs’ shelves scattered with canned goods, bags of Better Made potato chips, some suspect fresh meat, and a big cooler of Old English 800’s, Colt 45 and Stroh’s. You could always get a single, a light, and a 40 in a brown paper bag.

Squatter artists carried buckets of water up six floors to their ramshackled studios, broken window frames, cardboard filling where glass once was, entire floors, heavy pitted wood beams, and tin ceilings bent and falling fighting against the scraping freebooters. Art was done here. A pointillist dotting his half millimeter color across a massive canvas, months of work. Welded bumpers and rusted parts found in burned out and abandoned cars down the block, cut into lamp fixtures and tables with built-in ashtrays. A polka-dotted house of color and works of protest and identity shaped by a landscape of abandonment. Crumbling warehouses and factories full of rusted machines and stamping presses were the relic amphitheaters of the day. The sounds echoing through the carcasses as pigeons perch painting the steel girders and rats race in the shadows.

A small group of us lived downtown. Most buildings were dark, unoccupied. There were a couple old shotgun bars and an Irish pub, defunct theaters turned into dance clubs, strips clubs – some seedier than others, and a place that was a stop off for the rock and punk bands. The Ramones, Dead Kennedy’s, Iggy, R.E.M, and Echo & the Bunnymen, and then Marshall and that crew’s rap battles became legend. But we lived for the after-hours parties, dancing ‘til dawn. That music put a spell on people.”

Vince shook his head looking at Milo and then smiled up at Stacey, “You know what Mad Mike used to tell me? ‘Detroit was economically depressed but musically rich like a motherfucker.”

“Yes, it is, “ affirmed Stacey. “It’s that feel-good feel.”

“It must have been tough living in a place like that.” Milo said.

“Not at all. There was a freedom that came living in the empty shell of a city. Everything we knew was gone, so we created our own reality. It was the perfect backdrop for something to change the world.” Vince said.

“It was beautiful in that way. It was like a blank canvas for us to do anything we wanted.” Added Stacey. “There was a rawness here that was fertile ground. That’s how the music came. From the decay, the emptiness, robots taking jobs in the plants, and a soulfulness that will always be a part of here. It was all that.” She continued.

“You’re a fan, right?” Asked Stacey.

“Of course. Who isn’t? I love it, I really like the old stuff.” Milo responded.

“You know the music of Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May and Juan Atkins, right? They started it but there were many more. Eddie Fowlkes was right in there too. Anyway, they invented it. Techno. Right here in Detroit.

I’d been playing dance and house for years, then they…in their basements. They had grown up with the sounds of the Mojo, George Clinton, Kraftwerk and DJs like Kenny who spun magic at Heaven. This is way back. We’d been spinning since the ‘70’s, music you could feel. It was the bomb, we were making it up as we went.

In fact, Kenny Collier, gave them their first shot. You heard of him? Look him up. Anyway, it all came together and when people started hearing the sounds those three were putting down, they went crazy. I remember that like it was yesterday. They brought soul to the machine.” Stacey said.

“You got to understand, that music is Detroit music, it’s black music. It didn’t start in Berlin or London. It was right here. Those guys were pioneers, renegades of soul, I like to say. You got know where it came from before you can understand anything else. We had to wrestle that shit back from those Europeans. This is all Detroit. Motor City. Techno City.” She continued.

“I was just about to tell young Milo about the Institute and Centre Street.” Vince said.

“Ya, you got to. He needs to know.” Stacey said.

“Anyway, I’ve got to run. You listen to him. He’s like an Encyclopedia Brittanica.” She hugged Vince, kissed his cheek and walked over to the bar and greeted two young women.

“Pretty cool, huh. You just met a very special person. She’s literally the person responsible for getting House on the radio and she’s paved the way for so many, especially women DJ’s” said Vince as they sat down.

“That was dope. I’ll never forget that.” Milo said shaking his head. “What’s the Institute, and that other place?” asked Milo.

“Well, the Institute started everything. The Music Institute. Back in ’88. Downtown they had a building on Broadway, a tall space, simple, but what was cool was the DJ was a floor above the dance floor. I’ll never forget it. I think it had a single strobe light and the sound system was kind of slammed together. It was plywood benches, friends had painted murals on the walls, and they didn’t serve drinks, no alcohol, can you imagine that? Just water and juice. It was all about the music.”

“The crowd was from all over. Older folks, high school kids, gay, straight, black, white. Friday and Saturday nights it would be open from midnight to dawn. It was just five bucks.”

We had cool clubs before it, but there was something that went far beyond a nightclub or a party. It touched the spirit of the time and the things that kept folks apart, the racial shit, money, sexual preferences disappeared, all that shit just vanished.”

Alton Miller played Saturdays, when he played it was like he was giving a sermon of togetherness or something, I mean…people would be testifying, it lifted people and brought everyone together. Derrick would play Fridays, and it was out of this world. It’s where we, and it turns out the world, really heard techno. He killed it every night. Man, every night, he’d be doing stuff that well…people were out of their minds. And DJs and musicians came from all over the country and the world to check it out. I can still feel it and see it. It’s indescribable, really.”

“It was the first techno club in the world. Right here.”

“Damn. I would have loved to…are there any recordings or playlists from back then? Milo asked.

“I don’t so, I don’t think anyone even thought of it.” Vince replied.

“The place only lasted a year before it shut down.” Vince added. “Derrick once said, ‘It was like the Titanic, it died young and famous, and it’s always remembered.’”

“What happened?” Asked Milo.

“Let’s just say it was about the music, not making money.” Vince replied. “It closed in ’89. There were other places that followed but nothing like that for quite a while. Not until about 10, 11 years later when Centre Street opened.” Vince continued.

“Where was that? What was special about that so many years later?” Milo asked.

“Funny enough, it was right around the corner from where the Institute was. Lot of vacant buildings to choose from back then.” Vince said.

“What’s the best way to describe it? Got to understand we were, the music, was going through a resurgence of sorts, Derrick, Kevin, Carl, Kenny, all of them were playing all around the world. Techno and dance had exploded everywhere especially in Europe. These folks were playing in stadiums and huge festivals. It was still a scene here, it was ours after all, but not like it was, but when Centre Street opened it gave us all a new home.”

“I think it opened in 1999, it took over an old pub, gutted it, and creating something no one had ever seen around here.”

“How so?”, asked Milo.

“Well, if the Music Institute was the High Renaissance, the raw power of Brunelleschi’s Duomo, Centre Street was Baroque, the twisting theatrical form of Borromini. If you know your architecture and art history.” Vince said.

“What does that mean? Art history isn’t my thing.” Asked Milo.

“What I mean is that the Institute was raw power, the first, it expressed everything the people needed and the music demanded. And, Centre Street, well, it took that foundation and twisted and turned into something totally new.” Explained Vince.

“Centre Street was small and intimate, in a half-basement of a building. I guess they call it a Rathskeller, it was the lower level of an old German social club built in the 1880’s or something. It was pretty stunning inside, handmade tiles and all that. Original. Centre Street was a mix of things. It was club, lounge, a restaurant, people worked there during the day, kind of co-working before there was co-working. Kind of like this place is today, twenty-five years later. Then, it was like nothing in town. There were two rooms, the lounge had the bar, leather couches and these video screens on steel trolleys that moved, and the other was an old three or four lane bowling alley that was the dance floor. And it had an epic sound system, best around by far. I mean epic. The place could change depending upon the day and crowd. Could be super chill or full-on banging ‘til dawn. Lighting, video, VJs played you probably don’t remember VJ’s, the whole place could change, morph almost at a push of a button. Back then there was nothing like it. People jammed the place; they were thirsty for it.”

“What was cool, like the Institute, it was a place for everyone. There was a sense of belonging to it, it was the place we needed. It was a new ground, and old, all at the same time.”

“Everyone wanted to play there and did. All our folks loved coming home to play and when they did it, everybody came out. They sure did. If someone was in the country from Europe or wherever, Centre Street was a mandatory gig. They flew to Detroit. Everyone wanted in. It was just because of the vibe and spirit of the place. It only held a few hundred people and was like playing a private party. The list of people that played there is like who’s who of House and Techno.”

“Sounds amazing, it must have been a huge success.” Said Milo.

“It lasted two years, if that, and had to close.” Vince replied.

“Hold on a second. Both these places failed. Couldn’t make it? What lesson is that?” Milo asked.

“What places do people still talk about? 54, Paradise Garage, CBGB’s They were legendary or notorious for some reason or another. Here, they talk about the Music Institute and Centre Street. Why? Because they created something bigger and more important than the place itself. They were a moment in time that touched the collective consciousness of the people, this city and its music. It was a movement and that’s what made them special. And we’re still talking about almost 40 years later.”

“Now, of course, today we have the big Electronic Music Festival, been going on over 25 years. Tens of thousands of people come from all over the world every May. You been?” asked Vince.

“Anyway, I’m sure this was more than you asked for.” Vince went on, grabbed the two empty beer glasses and started to stand.

Milo stood up alongside Vince and said, “No, no this was very cool…I appreciate it all. I know now where I’m going.” He then looked across the room, “Connect to their consciousness…hmmm. I think I get that.”

“I’ve got to get to a neighborhood meeting, but whatever you do be gracious, be about something bigger than yourself. Whatever you do connect to the soul of the place and spirit of the people you do it for. Take a chance, it will make a difference no matter how long it lasts. Just remember even if it’s as quick as a lightning bolt, the vibrations will be felt for a very long time.” Vince said with gentle nod.

“Thanks so much, I’ll take this with me.” Said Milo as he turned and walked toward bright setting afternoon sun cutting through the entrance door.

“Zeitgeist.” Milo said to himself as he disappeared into light.